An energy reporter, for a

major daily business publication, contacted me to understand how electric

vehicle charging stations might become more readily available, particularly in

rural locales. She wondered whether the fast take up of new telecommunications

technologies, such as cellphones, cable television, and broadband, might offer

insights on what works to jump start market penetration.

Bear with

me as this apparently geeky subject offers insights on when electric vehicles might

reach critical mass, in time to achieve a significant reduction in greenhouse

gasses.

The

reporter intrigued me with a curious question whether the fast proliferation of

gas stations might provide a model for similar geographical market penetration

by electric vehicle charging stations. My

small collection of vintage gas station published road maps confirms she may be

onto something.

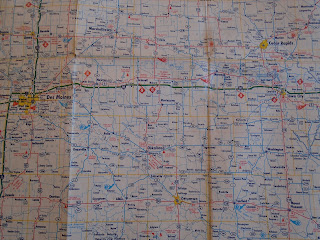

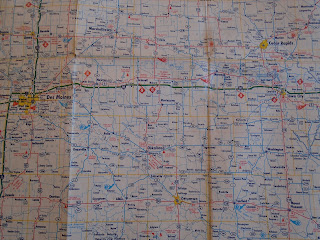

This late

1950s map of Iowa identifies locations where motorists can fill up with Skelly gasoline:

Marketing

101 suggests that a companies can bolster brand loyalty by offering a product

far and wide. The map identified

locations where motorists could find a Skelly station on the recently

constructed Interstate 80.

Access to EV

charging follows a similar chicken/egg challenge: car buyers will become more

inclined to buy an EV if they have confidence that access to charging stations

will not create FUD: fear, uncertainty, and doubt.

Several

parallels in telecom provide insights on what business models work.

Cellular Radio

Some

of you might remember the bad old days when a lack of vigilance when “roaming”

might result in a hefty and unexpected charge.

Before nationwide roaming, with “anytime, anywhere minutes,” the U.S.

had many standalone, “independent” operators, primarily serving ex urban and

rural locations. These carriers made a killing

by providing access to their networks by motorists speeding along a major

Interstate highway. Few noticed the icon

on their handsets (or bag phones) showing that a call was being handled by another

carrier.

The major

operators, such as Bell Atlantic, Pacific Telesis, Bell South, and Southwestern

Bell eventually executed roaming agreements with the small, independent

operators, thereby reducing or eliminating “non-network” roaming charges. The end to unexpected, extortionate roaming

charges helped expand subscribership and the eventual mergers and acquisitions that

now leave us with only three national carriers.

Cable Television

Unlike

cellular radio, cable television debuted in lots of rural areas at the same

time, or even before urban service.

First generation cable was labeled Community Antenna Television, typically

offered by local, “Mom and Pop” television sales and service ventures. These entrepreneurs offered cable television,

primarily to stimulate interest and demand for television sets.

CATV market

penetration occurred on small, town-by-town basis without coordination, or

accrual of scale economies. Rural

residence, starved for any broadcast television reception, gladly paid for

access to a few broadcast channels. Their

urban counterparts had free, off-air reception options. Only after cable operators embraced satellite

technology to deliver distant signals and new cable only content did national

penetration and subscribership speed up.

Broadband

High

speed Internet access provides a case study in a most desirable, but costly

technology largely unavailable in rural locales unless and until, private and

public actors subsidize access. This

technology has high startup costs that operators must bear before the first

dollar arrives. On the other hand, adding

an additional subscriber typically has much lower, so-called incremental costs,

especially for high density locales.

A private

venture might vertically integrate into the electric charging market to remove

FUD, generate brand loyalty, and stimulate vehicles sales. It might also install facilities using

proprietary standards resulting in incompatibility with EVs manufactured by

competitors.

A government

agency might want to stimulate demand, but typically the legislature must enact

laws creating tax incentives and financial subsidies. Unless and until incentives are anticipated and/or

funded a “Digital Divide” has resulted.

The Covid-19 pandemic underscores the consequences when broadband access

is unavailable or deemed too costly.

For

broadband and EV charging, state and federal governments may have to create

generous financial incentives to achieve anything close to ubiquitous access. Early adopters might not need as much

external funding, because they can anticipate market opportunities, such as when

a national hotel chain prioritizes the installation of charging stations.

In any

event, the past technology adoption models may offer insights on this new challenge.